Djibouti : pivot asymétrique entre deux stratégies, la Chine et les États-Unis

Djibouti occupe une position géographique exceptionnelle à la jonction de la mer Rouge, du golfe d’Aden et de l’océan Indien. Pourtant, dans la National Security Strategy 2025, ce pays et ses détroits adjacents sont absents. Cette omission n’est pas un oubli, mais le révélateur d’un changement doctrinal profond de la stratégie maritime américaine, désormais en contraste direct avec celle de la Chine.

1. La base américaine : Camp Lemonnier

Camp Lemonnier est la seule base militaire permanente des États-Unis en Afrique. Historiquement, elle a servi de plateforme pour le contre-terrorisme, le renseignement (ISR) et le soutien logistique régional.

Or, le rapport 2025 ne mentionne ni Djibouti ni Bab el-Mandeb, confirmant une dépriorisation des théâtres maritimes périphériques au profit des zones décisives de rivalité de puissance (p.15–16, section The Regions).

Cette absence est cohérente avec la doctrine de “burden-shifting”, selon laquelle les États-Unis refusent désormais de jouer le rôle de « police maritime globale » (p.11–12, section Priorities – Burden-Sharing and Burden-Shifting).

- Camp Lemonnier demeure utile, mais comme base de soutien tactique, non comme pivot stratégique.

2. La base chinoise : PLA Support Base Djibouti

À l’inverse, la base chinoise de Djibouti constitue un jalon stratégique central dans l’expansion maritime de Pékin. Elle soutient les opérations navales de la PLAN en mer Rouge et dans le golfe d’Aden, tout en sécurisant les routes commerciales Chine–Europe.

Cette logique correspond exactement à ce que le rapport américain identifie comme une stratégie adverse fondée sur le contrôle des chaînes d’approvisionnement et des flux mondiaux, notamment via des investissements civilo-militaires (p.20–22, section Asia – Economics: The Ultimate Stakes).

- Là où Washington hiérarchise et se retire des marges, Pékin additionne les points d’appui.

3. Mer de Chine méridionale (South China Sea)

La mer de Chine méridionale est décrite comme une artère vitale du commerce mondial, par laquelle transite environ un tiers du commerce maritime global (p.23–24, section Deterring Military Threats).

Le rapport souligne qu’un contrôle hostile de cette zone permettrait d’imposer des péages ou de fermer l’accès maritime à volonté.

C’est le théâtre maritime le plus stratégique du document, directement lié à la dissuasion militaire, à l’économie américaine et au système d’alliances (p.19–24).

4. Détroit d’Ormuz (Strait of Hormuz)

Le détroit d’Ormuz est cité explicitement parmi les intérêts vitaux permanents des États-Unis (p.28–29, section The Middle East). Il est présenté comme un chokepoint énergétique critique devant impérativement rester ouvert.

Cependant, le rapport l’inscrit dans une logique de gestion défensive, cohérente avec le désengagement relatif du Moyen-Orient au profit de l’Indo-Pacifique (p.27–28).

- Ormuz demeure important, mais n’est plus structurant.

5. Mer Rouge (Red Sea)

La mer Rouge n’est mentionnée qu’une seule fois, uniquement comme voie maritime devant rester navigable (p.28–29). Aucun acteur, menace ou scénario n’y est associé.

Cette mention minimale confirme que la mer Rouge est perçue comme un corridor fonctionnel, non comme un théâtre stratégique autonome. L’absence totale de Bab el-Mandeb et du golfe d’Aden renforce cette lecture.

6. Le rôle des alliés (Israël, France, Italie, etc.)

Le rapport insiste sur le recours accru aux alliés régionaux pour la stabilité locale, conformément au principe de partage des charges (p.11–13).

Israël est explicitement cité comme un pilier de la sécurité régionale au Moyen-Orient (p.28–29) : « Les États-Unis auront toujours des intérêts fondamentaux à garantir que les approvisionnements énergétiques du Golfe ne tombent pas entre les mains d’un ennemi déclaré, que le détroit d’Hormuz reste ouvert, que la mer Rouge demeure navigable, que la région ne serve ni d’incubateur ni d’exportateur de terrorisme visant les intérêts américains ou le territoire national, et qu’Israël reste en sécurité. »

Les alliés européens, notamment la France et l’Italie, sont implicitement appelés à assumer davantage de responsabilités maritimes dans les zones périphériques, y compris en mer Rouge et en Afrique (p.12, Burden-Sharing Network).

- Cette externalisation explique le maintien des bases européennes à Djibouti, pendant que les États-Unis se recentrent ailleurs.

7. Conclusion

La comparaison entre la stratégie américaine et la stratégie chinoise révèle une asymétrie fondamentale :

- Les États-Unis concentrent leur puissance sur les nœuds décisifs de l’équilibre mondial, principalement en Indo-Pacifique.

- La Chine construit une présence maritime cumulative, sécurisant les flux à long terme.

Djibouti incarne cette divergence :

vital pour la Chine, tolérable pour les États-Unis.

La confrontation maritime décisive ne s’y jouera pas. Elle se jouera là où les États-Unis ont choisi d’investir pleinement : la mer de Chine méridionale.

Référence principale

National Security Strategy of the United States of America, November 2025.

Hassan Cher

The English translation of the article in French.

Djibouti: An Asymmetric Pivot Between Two Strategies — China and the United States

Djibouti occupies an exceptional geographic position at the junction of the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, and the Indian Ocean. Yet in the 2025 National Security Strategy, neither Djibouti nor its adjacent straits are mentioned. This omission is not an oversight; it reveals a profound doctrinal shift in U.S. maritime strategy, now in direct contrast with that of China.

1. The U.S. Base: Camp Lemonnier

Camp Lemonnier is the only permanent U.S. military base in Africa. Historically, it has served as a platform for counterterrorism operations, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), and regional logistical support.

However, the 2025 report makes no reference to either Djibouti or the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, confirming a deprioritization of peripheral maritime theaters in favor of decisive zones of great-power rivalry (pp. 15–16, The Regions section).

This absence aligns with the doctrine of “burden-shifting,” under which the United States no longer seeks to act as the world’s “global maritime police” (pp. 11–12, Priorities – Burden-Sharing and Burden-Shifting).

➤ Camp Lemonnier remains useful, but as a tactical support base rather than a strategic pivot.

2. The Chinese Base: PLA Support Base Djibouti

By contrast, China’s Djibouti base constitutes a central strategic milestone in Beijing’s maritime expansion. It supports PLA Navy (PLAN) operations in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden while securing China–Europe commercial sea lanes.

This logic corresponds precisely to what the U.S. report identifies as an adversarial strategy based on control of supply chains and global flows, notably through civil-military investments (pp. 20–22, Asia – Economics: The Ultimate Stakes).

➤ Where Washington prioritizes and withdraws from the margins, Beijing accumulates footholds.

3. South China Sea

The South China Sea is described as a vital artery of global trade, through which approximately one-third of worldwide maritime commerce transits (pp. 23–24, Deterring Military Threats).

The report emphasizes that hostile control of this area would enable the imposition of tolls or the selective closure of maritime access at will.

It is the most strategically significant maritime theater in the document, directly linked to military deterrence, the U.S. economy, and alliance systems (pp. 19–24).

4. Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is explicitly cited among the permanent vital interests of the United States (pp. 28–29, The Middle East). It is presented as a critical energy chokepoint that must remain open.

Nevertheless, the report situates it within a defensive management framework, consistent with the relative disengagement from the Middle East in favor of the Indo-Pacific (pp. 27–28).

➤ Hormuz remains important, but it is no longer structurally decisive.

5. Red Sea

The Red Sea is mentioned only once, solely as a maritime route that must remain navigable (pp. 28–29). No actors, threats, or scenarios are associated with it.

This minimal reference confirms that the Red Sea is viewed as a functional corridor rather than an autonomous strategic theater. The complete absence of Bab el-Mandeb and the Gulf of Aden reinforces this interpretation.

6. The Role of Allies (Israel, France, Italy, etc.)

The report emphasizes increased reliance on regional allies for local stability, in line with the burden-sharing principle (pp. 11–13).

Israel is explicitly cited as a pillar of regional security in the Middle East (pp. 28–29):

“The United States will always have fundamental interests in ensuring that Gulf energy supplies do not fall into the hands of a declared enemy, that the Strait of Hormuz remains open, that the Red Sea remains navigable, that the region does not serve as an incubator or exporter of terrorism targeting U.S. interests or the homeland, and that Israel remains secure.”

European allies—particularly France and Italy—are implicitly called upon to assume greater maritime responsibilities in peripheral zones, including the Red Sea and Africa (p. 12, Burden-Sharing Network).

➤ This outsourcing explains the continued presence of European bases in Djibouti, while the United States refocuses elsewhere.

7. Conclusion

The comparison between U.S. and Chinese strategies reveals a fundamental asymmetry:

- The United States concentrates its power on decisive nodes of the global balance, primarily in the Indo-Pacific.

- China builds a cumulative maritime presence, securing long-term flows.

Djibouti embodies this divergence:

Vital for China, tolerable for the United States.

The decisive maritime confrontation will not take place there. It will occur where the United States has chosen to invest fully: the South China Sea.

Primary Reference

National Security Strategy of the United States of America, November 2025.

Hassan Cher

Previous Article

Previous Article Next Article

Next Article Mount Fuji Japan

Mount Fuji Japan  Somalie/Djibouti : Comment Al-shabab a infiltré le système américain de coopération pour la lutte contre le terrorisme grâce au régime Djiboutien.

Somalie/Djibouti : Comment Al-shabab a infiltré le système américain de coopération pour la lutte contre le terrorisme grâce au régime Djiboutien.  Somalie : La Somalie a battu le Soudan du Sud et remporte le CECAFA U17 de 2022.

Somalie : La Somalie a battu le Soudan du Sud et remporte le CECAFA U17 de 2022.  Djibouti/Afar : Ismael Omar Guelleh vient de donner l’ordre d’arrestation du sultan de Tadjourah, Ahmed Chehem Ahmed.

Djibouti/Afar : Ismael Omar Guelleh vient de donner l’ordre d’arrestation du sultan de Tadjourah, Ahmed Chehem Ahmed.  Union Africaine : Guelleh soutient Mahamoud Ali Youssouf, mais privilégie une victoire stratégique de Raila Odinga pour ses intérêts en Afrique de l’Est.

Union Africaine : Guelleh soutient Mahamoud Ali Youssouf, mais privilégie une victoire stratégique de Raila Odinga pour ses intérêts en Afrique de l’Est.  Djibouti : Guelleh arme des milices et recrute des terroristes pour son 6e mandat, prêt à enflammer la guerre civile et paralyser Bab-el-Mandeb

Djibouti : Guelleh arme des milices et recrute des terroristes pour son 6e mandat, prêt à enflammer la guerre civile et paralyser Bab-el-Mandeb  Djibouti / Droits de l’homme: Tortures, viols, détentions arbitraires, maltraitance et privation des droits fondamentaux sous…

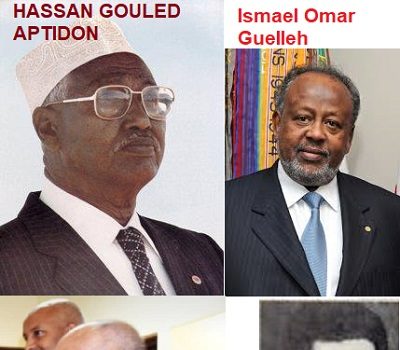

Djibouti / Droits de l’homme: Tortures, viols, détentions arbitraires, maltraitance et privation des droits fondamentaux sous…  Djibouti/attentat de l’Historil : Gouled, Guelleh et Adouani, les commanditaires et exécutant de l’attentat terroriste de 1987 à Djibouti.

Djibouti/attentat de l’Historil : Gouled, Guelleh et Adouani, les commanditaires et exécutant de l’attentat terroriste de 1987 à Djibouti.