Bab el-Mandeb: l’interconnexion stratégique des trafics d’armes entre l’Iran, la Somalie, Djibouti et les Houthis du Yémen

Les récents témoignages recueillis auprès de l’équipage d’un boutre intercepté par les Forces de Résistance Nationale yéménites (NRF) le 16 juillet 2025 révèlent, avec une précision inédite, les rouages d’un réseau international de trafic d’armes sophistiquées. Ce maillage complexe, qui relie Téhéran, la Corne de l’Afrique et les côtes de la mer Rouge, alimente directement les capacités militaires des rebelles Houthis, consolidant leur position dans la guerre civile yéménite.

1. Une interception stratégique

Le boutre arraisonné, parti de Djibouti et à destination de Hodeida, transportait une cargaison massive d’armement en provenance d’Iran. Cette saisie illustre la persistance et la sophistication des opérations logistiques qui soutiennent l’effort de guerre houthi, malgré les sanctions internationales et la surveillance maritime accrue.

Les forces de Tariq Saleh, membre du Conseil de Direction Présidentiel (CDP), ont mis la main sur des missiles, pièces de drones et équipements de communication militaires, confirmant l’implication directe de réseaux iraniens.

2. Des itinéraires maritimes multipoints

Les témoignages détaillent plusieurs schémas d’acheminement :

- Ligne directe Iran–Yémen : des cargaisons quittent le port iranien de Bandar Abbas pour rejoindre directement Al-Salif, au Yémen.

- Transbordement via la Somalie : certaines livraisons passent par Ras Qouray, un point côtier somalien où les armes sont transférées d’un navire iranien vers des embarcations plus petites, moins détectables, avant d’atteindre Al-Salif.

- Relais logistique de Djibouti : un volume considérable d’armes (douze cargaisons recensées par les témoins repentis) est expédié depuis Djibouti vers le Yémen, utilisant les infrastructures portuaires et la proximité géographique pour faciliter les transferts.

Cette diversification des routes rend le trafic résilient face aux interceptions navales et brouille les pistes d’approvisionnement.

3. Les acteurs du réseau

Le cœur opérationnel repose sur trois pôles :

- Les Houthis : destinataires finaux, ils coordonnent les expéditions, financent les trajets et assurent la distribution des armes dans les zones de combat.

- Les intermédiaires maritimes : Qawlaysato (hauts responsables djiboutiens et somaliens), les capitaines de boutres, pêcheurs et contrebandiers servent de relais logistiques, souvent rémunérés par cargaison ou par voyage, et opèrent en zone grise entre activités légales et clandestines.

- Les facilitateurs iraniens : selon les témoignages, des navires iraniens livrent directement ou indirectement les armes, ce qui confirme l’alignement stratégique entre Téhéran et les Houthis.

4. Les types d’armes et leur impact stratégique

Les cargaisons interceptées comprennent :

- Missiles antichars et antiaériens.

- Drones armés ou d’observation, avec pièces détachées et systèmes de guidage.

- Munitions diverses, armes légères et équipements de communication chiffrés.

Ces livraisons renforcent considérablement la capacité des Houthis à mener des attaques asymétriques, notamment contre les navires marchands en mer Rouge et les infrastructures militaires yéménites.

5. Les hubs africains comme pivots

La Somalie et Djibouti jouent un rôle central pour deux raisons :

- Proximité maritime : leur localisation stratégique permet de réduire la durée des trajets et de contourner les zones de patrouille.

- Vulnérabilité institutionnelle : l’instabilité politique en Somalie et l’implication des hauts responsables des états de Djibouti et de la Somalie agissant sous la couverture de la mafia Qawlaysato offrent un environnement propice au masquage des cargaisons illicites.

Des liens informels entre contrebandiers somaliens et réseaux houthistes permettent de fluidifier les échanges, tandis que Djibouti, bien que doté d’un port international contrôlé, voit ses eaux côtières exploitées pour des opérations discrètes avec la complicité des hauts responsables du régime au pouvoir.

6. Une architecture en couches

Le trafic ne repose pas sur une chaîne linéaire, mais sur une structure modulaire :

- Des fournisseurs d’armes (principalement iraniens) assurent l’approvisionnement.

- Des cellules logistiques indépendantes gèrent chaque segment du trajet, limitant les risques de compromission globale.

- Des points de rechargement (ports secondaires, mouillages isolés) permettent de fractionner les cargaisons, rendant plus difficile leur détection.

7. Les enjeux régionaux

Ce trafic contribue à :

- Prolonger le conflit yéménite en fournissant un flux constant d’armement.

- Mettre en danger la liberté de navigation dans le détroit de Bab el-Mandeb.

- Renforcer l’influence iranienne dans la région, au détriment des alliés occidentaux et arabes opposés aux Houthis.

Il nourrit également une économie parallèle où se mêlent contrebande d’armes, de carburant et d’autres marchandises, ancrant des réseaux criminels dans le tissu socio-économique local.

8. Une réponse internationale limitée

Malgré les patrouilles navales internationales, les sanctions de l’ONU et les opérations de contrôle, les Houthis continuent à s’approvisionner. Les raisons :

- Faible coordination entre États riverains de la mer Rouge.

- Implication des hauts responsables des états de Djibouti et de la Somalie œuvrant sous la couverture de la mafia Qawlaysato.

- Usage de navires traditionnels (boutres) peu suspects et difficiles à intercepter sans renseignement préalable.

- Fragmentation volontaire des cargaisons pour réduire les pertes en cas d’interception.

9. Témoignages : l’aveu des passeurs

Les récits des marins capturés apportent un éclairage rare :

- Certains reconnaissent avoir travaillé depuis plusieurs années pour les Houthis, effectuant des voyages réguliers depuis Djibouti, la Somalie ou l’Iran.

- Les paiements sont souvent effectués en liquide ou en nature, ce qui complique la traçabilité financière.

- Les itinéraires sont modifiés à la dernière minute en fonction de la présence de navires de guerre étrangers.

10. Conclusion : un réseau adaptable et résilient

L’interconnexion entre l’Iran, la Somalie, Djibouti et les Houthis constitue un modèle avancé de trafic maritime clandestin. Sa réussite repose sur :

- Une multiplicité de routes maritimes.

- Une décentralisation des opérations.

- L’exploitation des failles géopolitiques et institutionnelles régionales.

Tant que les Houthis disposeront de ce soutien logistique, les perspectives de stabilisation au Yémen resteront fragiles. Une stratégie efficace de lutte contre ce trafic devrait combiner renseignement maritime, coopération régionale renforcée, sanctions ciblées à l’égard des hauts responsables djiboutiens et somaliens impliqués dans ces trafics et assèchement des flux financiers.

Hassan Cher

The English translation of the article in French.

Bab el-Mandeb: the strategic interconnection of arms trafficking between Iran, Somalia, Djibouti and the Houthis in Yemen

Recent testimony gathered from the crew of a dhow intercepted by the Yemeni National Resistance Forces (NRF) on 16 July 2025 reveals, with unprecedented precision, the workings of an international network of sophisticated arms trafficking. This complex network, which links Tehran, the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea coast, feeds directly into the military capabilities of the Houthi rebels, consolidating their position in the Yemeni civil war.

1. A strategic interception

The dhow boarded, bound for Hodeida from Djibouti, was carrying a massive cargo of weapons from Iran. This seizure illustrates the persistence and sophistication of the logistical operations supporting the Houthi war effort, despite international sanctions and increased maritime surveillance.

The forces of Tariq Saleh, a member of the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), got their hands on missiles, drone parts and military communications equipment, confirming the direct involvement of Iranian networks.

2. Multi-point maritime routes

The testimonies detail several routing patterns:

– Direct Iran-Yemen line: shipments leave the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas and go directly to Al-Salif in Yemen.

– Transhipment via Somalia: some deliveries pass through Ras Qouray, a Somali coastal point where the weapons are transferred from an Iranian ship to smaller, less detectable boats, before reaching Al-Salif.

– Djibouti as a logistical hub: a considerable volume of weapons (twelve shipments identified by eyewitnesses) is shipped from Djibouti to Yemen, using the port infrastructure and geographical proximity to facilitate the transfers.

This diversification of routes makes the traffic resilient to naval interception and blurs the supply routes.

3. The players in the network

The operational core is based on three poles:

– The Houthis: as the final recipients, they coordinate the shipments, finance the routes and ensure the distribution of the weapons in the combat zones.

– Maritime intermediaries: Qawlaysato (senior Djiboutian and Somali officials), dhow captains, fishermen and smugglers act as logistical relays, often paid per cargo or per journey, and operate in the grey zone between legal and illegal activities.

– Iranian facilitators: according to eyewitness accounts, Iranian ships are directly or indirectly delivering the weapons, confirming the strategic alignment between Tehran and the Houthis.

4. Types of weapons and their strategic impact

Intercepted shipments include:

– Anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles.

– Armed or observation drones, with spare parts and guidance systems.

– Various munitions, light weapons and encrypted communications equipment.

These deliveries considerably strengthen the capacity of the Houthis to carry out asymmetric attacks, particularly against merchant ships in the Red Sea and Yemeni military infrastructure.

5. African hubs as pivots

Somalia and Djibouti play a central role for two reasons:

1. Proximity by sea: their strategic location means they can reduce journey times and bypass patrol zones.

2. Institutional vulnerability: political instability in Somalia and the involvement of high-ranking officials from Djibouti and Somalia acting under cover of the Qawlaysato mafia provide an environment conducive to the concealment of illicit shipments.

Informal links between Somali smugglers and Houthist networks allow trade to flow smoothly, while Djibouti, despite having a controlled international port, sees its coastal waters exploited for discreet operations with the complicity of senior officials of the regime in power.

6. A layered architecture

Trafficking is not based on a linear chain, but on a modular structure:

– Arms suppliers (mainly Iranian) provide the supplies.

– Independent logistics units manage each segment of the route, limiting the risk of overall compromise.

– Reloading points (secondary ports, isolated anchorages) allow the cargo to be split up, making it more difficult to detect.

7. Regional issues

This traffic contributes to :

– Prolonging the Yemeni conflict by providing a constant flow of weapons.

– Endangering freedom of navigation in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait.

– Strengthening Iranian influence in the region, to the detriment of Western and Arab allies opposed to the Houthis.

It is also fuelling a parallel economy in which arms, fuel and other goods are smuggled, anchoring criminal networks in the local socio-economic fabric.

8. A limited international response

Despite international naval patrols, UN sanctions and control operations, the Houthis continue to obtain supplies. The reasons:

– Poor coordination between states bordering the Red Sea.

– Involvement of senior officials from Djibouti and Somalia working under cover of the Qawlaysato mafia.

– Use of traditional vessels (dhows) that are not very suspicious and difficult to intercept without prior intelligence.

– Deliberate fragmentation of cargo to reduce losses in the event of interception.

9. Testimonies: the admission of smugglers

The accounts of captured sailors shed a rare light:

– Some admit to having worked for the Houthis for several years, making regular trips from Djibouti, Somalia or Iran.

– Payments were often made in cash or in kind, which made it difficult to trace the money.

– Itineraries are changed at the last minute depending on the presence of foreign warships.

10. Conclusion: an adaptable and resilient network

The interconnection between Iran, Somalia, Djibouti and the Houthis is an advanced model of clandestine maritime traffic. Its success is based on :

– A multiplicity of maritime routes.

– Decentralised operations.

– Exploiting regional geopolitical and institutional weaknesses.

As long as the Houthis have this logistical support, the prospects for stabilising Yemen will remain fragile. An effective anti-trafficking strategy should combine maritime intelligence, enhanced regional cooperation, targeted sanctions against senior Djiboutian and Somali officials involved in trafficking and the drying up of financial flows.

Hassan Cher

Liens/Links: 1- https://www.hch24.com/actualites/07/2025/djibouti-mer-rouge-les-forces-de-resistance-nationale-yemenite-interceptent-des-armes-en-provenance-de-djibouti-et-washington-et-paris-pressent-le-regime-de-guelleh/, 2-https://www.hch24.com/actualites/07/2025/somaliland-analyse-du-risque-dusage-detourne-du-peroxyde-dhydrogene-dossier-msg-group-of-companies/, 3- https://www.hch24.com/actualites/08/2025/mer-rouge-le-reseau-secret-du-trafic-darmes-iranien-aux-houthis-via-djibouti-et-somalie-devoile-par-des-marins-repentis/

Previous Article

Previous Article Next Article

Next Article Djibouti/Ericsson/Suède : Ericsson, soupçonnée d’avoir versé des pots-de-vin à de hauts responsables djiboutiens…

Djibouti/Ericsson/Suède : Ericsson, soupçonnée d’avoir versé des pots-de-vin à de hauts responsables djiboutiens…  Somalie : Y a-t-il un projet d’assassinat caché ourdi contre Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud ?

Somalie : Y a-t-il un projet d’assassinat caché ourdi contre Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud ?  Djibouti/France : La compagne anti-française menée en catimini par Ismaël Omar Guelleh

Djibouti/France : La compagne anti-française menée en catimini par Ismaël Omar Guelleh  Djibouti/USA : La Naval Criminal Investigative Service à Djibouti pour enquêter sur les répressions contre les travailleurs civils de la base militaire américaine…

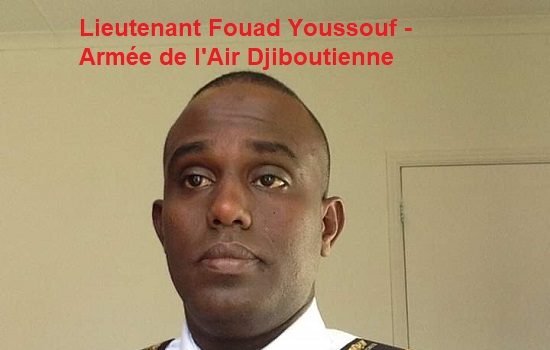

Djibouti/USA : La Naval Criminal Investigative Service à Djibouti pour enquêter sur les répressions contre les travailleurs civils de la base militaire américaine…  Djibouti : Le lieutenant Fouad Youssouf Ali est transféré à la prison centrale Gabode depuis le 26 avril 2020 d’après le régime de Guelleh.

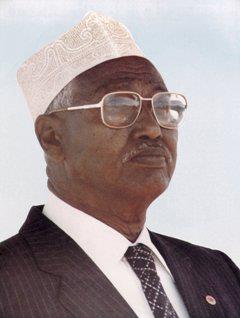

Djibouti : Le lieutenant Fouad Youssouf Ali est transféré à la prison centrale Gabode depuis le 26 avril 2020 d’après le régime de Guelleh.  Djibouti/Éthiopie : Les biens mal acquis de Hassan Gouled Aptidon et des membres du régime de Guelleh en Éthiopie.

Djibouti/Éthiopie : Les biens mal acquis de Hassan Gouled Aptidon et des membres du régime de Guelleh en Éthiopie.  Djibouti/Chine : un échange volontaire d’une base navale militaire contre des avantages financiers et l’appui d’un régime pérenne à Djibouti.

Djibouti/Chine : un échange volontaire d’une base navale militaire contre des avantages financiers et l’appui d’un régime pérenne à Djibouti.